Mapping Watershed Communities – A Working Model

THE BACKSTORY:

In the early 2000’s, I organized an arts-based environmental education program that involved camping on the banks of the Haw River for weeks at time. Living in temporary tent cities with artists, performers, and naturalists – all volunteer citizen diplomats working together to create a sense of place for children through hands-on engagement in the natural world – solidified my conviction to make art that educates and inspires stewardship.

In 2004, I went to graduate school with the intention of developing my own community-based creative practice and the river came with me. Its image, which offers both a literal and metaphorical expression of interconnectedness, became my primary visual language. I’ve spent more than a decade refining and finding confidence in my artistic voice, and I’ve only just begun the process of adding strength to this voice through community engagement.

THE WORK:

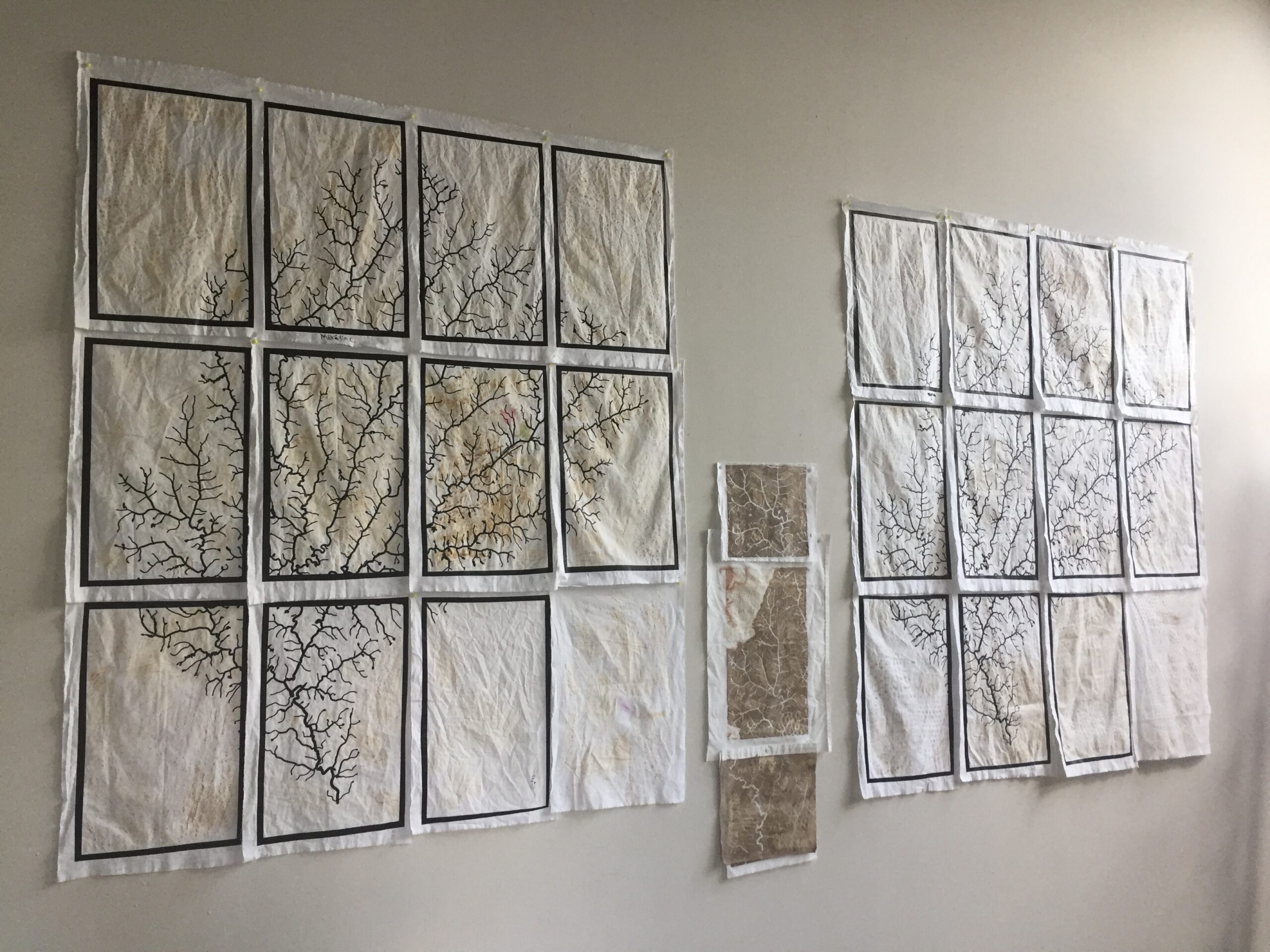

In the summer of 2019, I spent 10 weeks as an artist-in-residence at McColl Center in Charlotte, North Carolina. While there, I experimented with the design and implementation of ecoart mapping workshops at Studio 345, a free creative arts program for Charlotte-area students. Over the course of four sessions, I collaborated with both middle and high school students to create two maps of Charlotte’s urban streams. Together, we transformed rocks and soil into artful expressions of place while students gained a personal understanding of urban water ecology and the implications of our interdependence. The local watersheds of Charlotte served not only as subject matter, but also as a framework for thinking about boundaries, notions of home, and definitions of community.

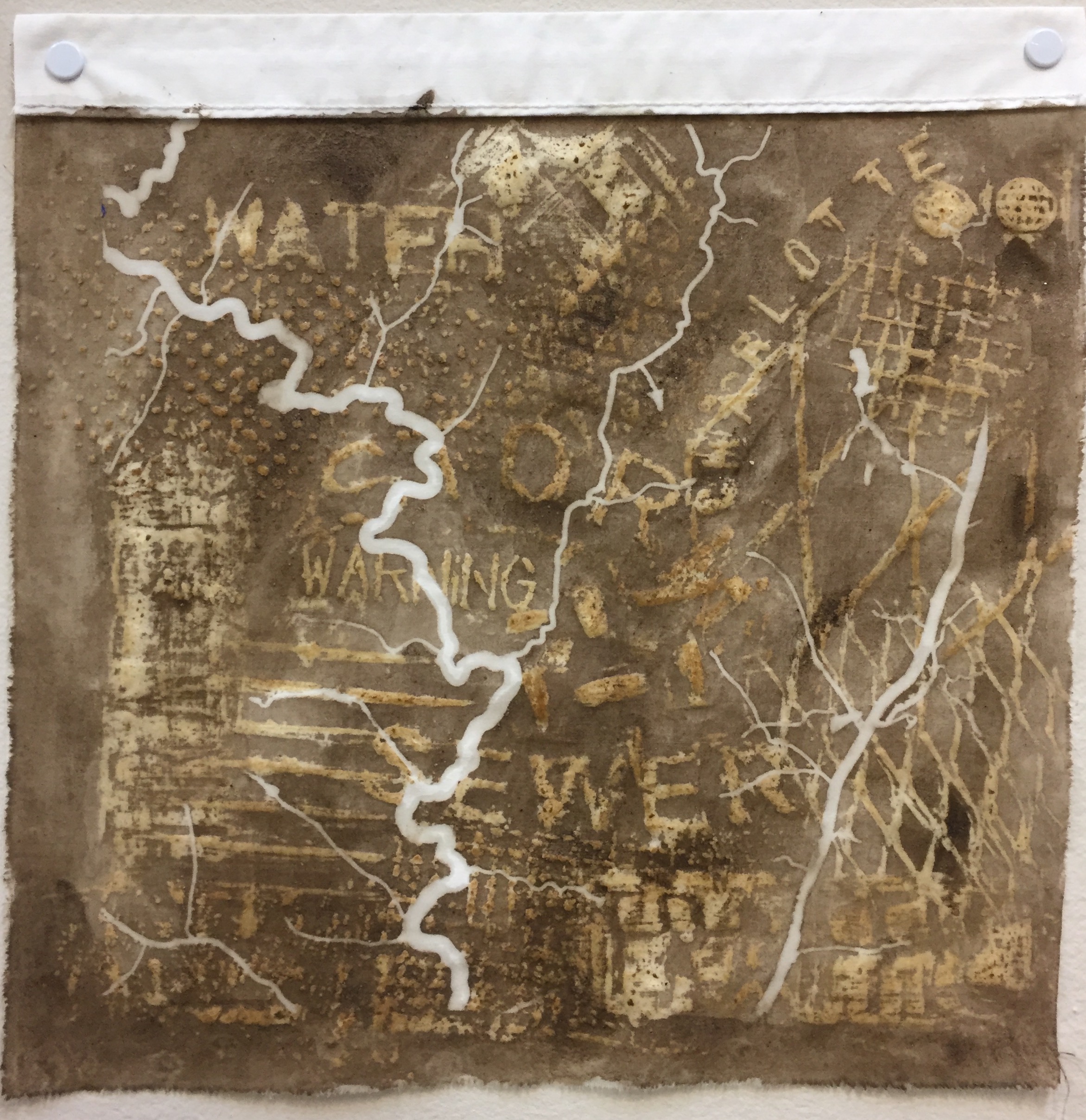

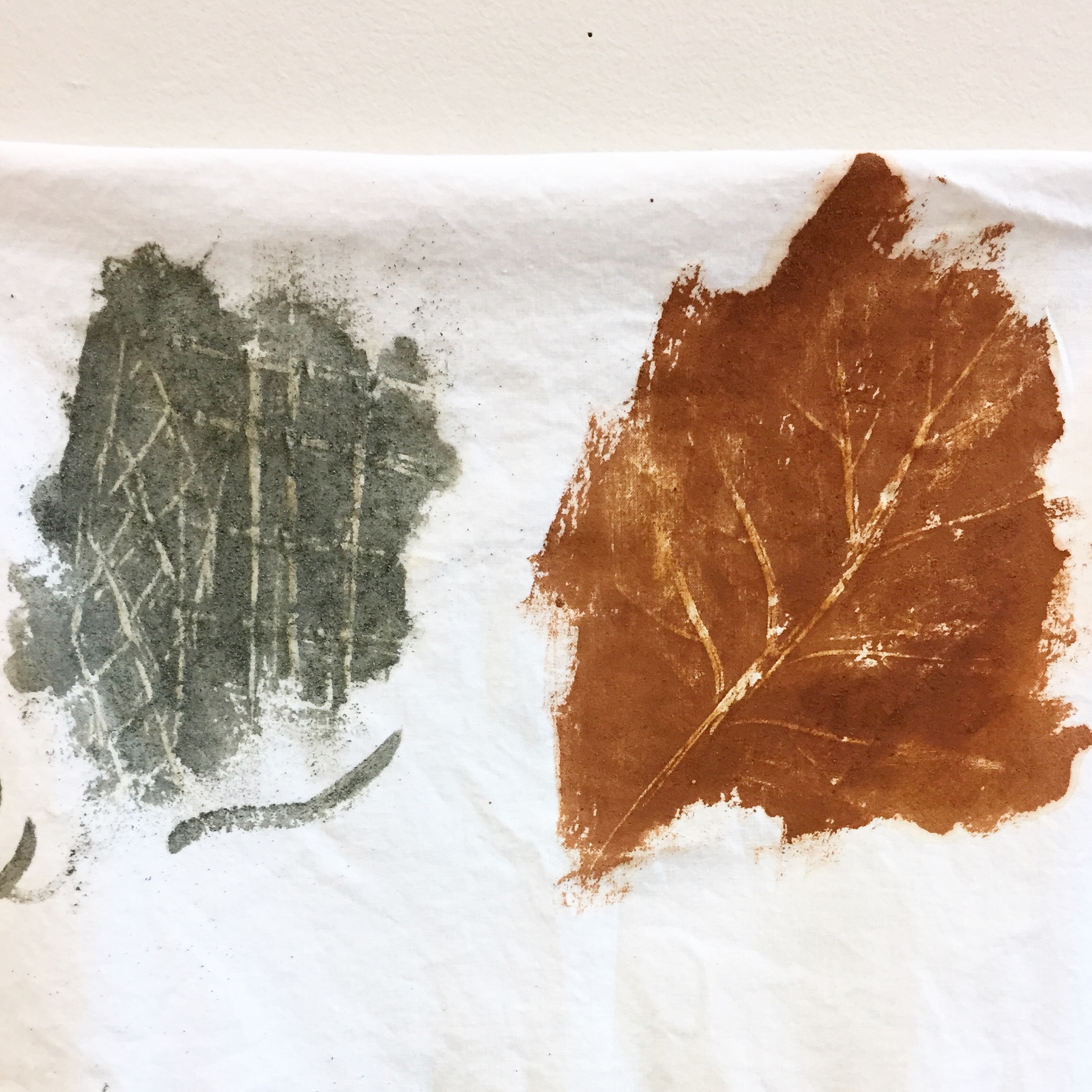

The resulting paintings are multi-sectional maps of the Sugar Creek basin made from the textures and colors of Charlotte’s urban landscape. The middle school group made rubbings of natural textures at Fourth Ward Park and painted over them with red clay pigment collected along the Little Sugar Creek Greenway. The high school group made rubbings of industrial textures in the streets around Spirit Square and painted over them with blue granite collected at a Vulcan Materials quarry in Pineville. Together, these two seemingly identical maps exhibit subtle differences and collectively comment on the varied systems that influence the nature and quality of Charlotte’s waterways.

Sugar Creek / Spirit Square (L) and Sugar Creek / Fourth Ward Park (R), 2019, 5’h x 5’w, blue granite, clay, water, gum arabic, and wax on cotton fabric

THE PROCESS:

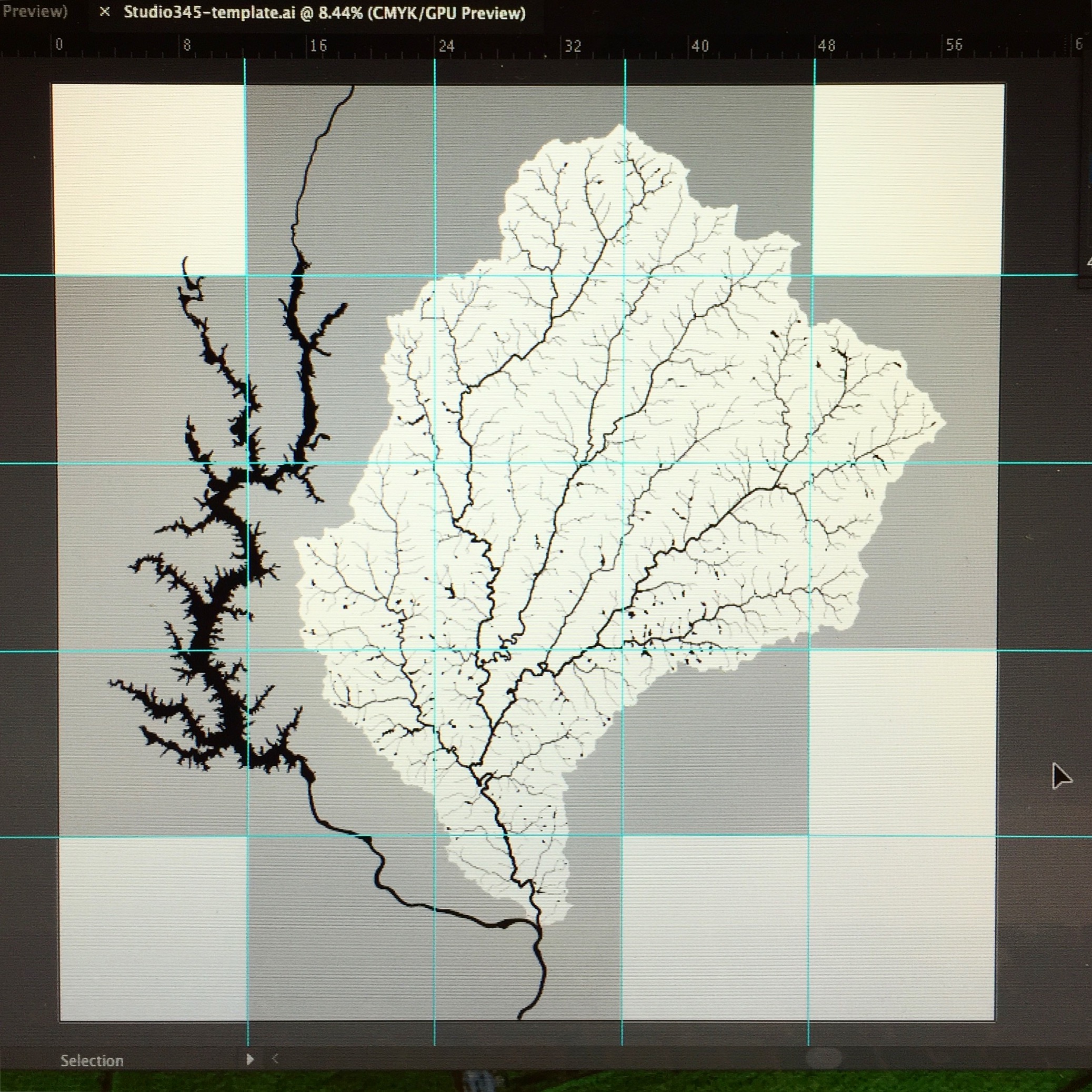

1. My work always starts on the computer with stream data in ArcMap, a geographic information systems (GIS) mapping software. I use a process of selection, elimination, and emphasis to simplify the data for artistic use. I then export it to Adobe Illustrator, where I complete the majority of file clean-up.

For this particular project, I knew that I’d be working with about 15-20 students in each age group, so I decided to divide the image into enough pieces that each participant could “own” a section of the map, giving them an opportunity to individually contribute to the larger picture of their watershed community. I chose an urban stream network big enough that almost every participant lived within its boundaries so that they could all relate to and have a stake in the process.

2. I collect rocks and soil in the field. I love being outside, walking along stream banks, sometimes even wading into the streams. I feel an incredible sense of wonder in nature and there are so many moments of joy and play while I’m out collecting raw materials. I wish that I had been able to bring the students from Studio 345 out into the “wild” with me. Unfortunately, organizing an outing of this scope was too complicated logistically in this instance, so I collected raw materials on my own.

3. I bring collected samples back to the studio to process them. This means rinsing rocks, separating them by color, drying clay soil, and grinding rocks with a power rock crusher or by hand with a mortar and pestle depending on their consistency. Sifting, grinding, sifting, sorting…it’s a long process. I was able to share some pieces of this process with the students. The middle schoolers were particularly enamored with grinding and sifting soil, and I was amazed at how quickly the material was transformed with so many hands working together. I decided that I will have to employ an army of children in my studio from now on (ha!).

4. I generally mix the resulting pigments with water and gum arabic to create watercolor paints. In developing this collaborative project, I wanted to create a dynamic image using simple processes that could be successfully executed by participants of almost any age group and skill level. I decided to combine rubbings (frottage) and watercolor to create texture via wax resist. I had never made crayons before, so I spent some time experimenting with several recipes until I found one that left enough residue on cotton fabric to resist paint well.

5. Using the files I’ve cleaned up in Illustrator and a plotter, I create vinyl masks that are adhered to the substrate before any other media is applied. These masks are ultimately removed, but are essential in defining streams and watershed boundaries in the creation of the work. Almost every section of these maps had to be masked with vinyl in 2 parts – first, the streams inside the watershed were masked so that they would not receive wax from the crayon rubbings (all other surfaces received wax). Then, after the rubbings were finished, the areas outside of the watershed, which did not receive paint got a second vinyl mask. Thankfully, McColl gave me a fantastic studio assistant/intern, Elizabeth Hammock, who helped me apply the vinyl. She was also a fibers major at UNC Charlotte and very adept with a sewing machine (WIN!). She assembled all of the individual map sections into two large finished works. Having Elizabeth in the studio with me 2 days a week was an incredible gift. I don’t know how I would have completed this project without her able hands and eager attitude.

Aside from the making, I organized a few short exercises and an artist talk to get the students thinking about their work in the context of some larger issues about mapping, community, and ecology. Giving them a chance to think critically and to recognize that art can be used as a tool for social change was equally as important as the final products created during our time together. The short video below documents the community aspects of the project and was produced by a student teaching assistant at Studio 345. Bonus: You get to see me as a pregnant lady!

Also, the gallery below it includes images that further describe the process outlined above.

IMAGE GALLERY:

-

(1) File Clean-up in Adobe Illustrator -

(2) Collecting Samples -

(3) Processing Samples in the Studio -

(3) Sorting Pigments in the Studio -

(4) Natural Pigment Crayons -

Studio Experiment / Process Development -

Final Colors Test -

(5) Vinyl Masking Fabric -

Sugar Creek maps – rubbings finished -

Sugar Creek / Fourth Ward Park – in progress -

Sugar Creek / Fourth Ward Park, detail -

Sugar Creek / Spirit Square, detail

1 Comment

Permalink

This is terrific. So unique and original. Keep doing this amazing work.

Comments are closed.